Nothing to declare: The Illusion of Transparency in South Africa’s Parliamentary Disclosures

MP disclosures lack accessibility and consistency, weakening oversight. A structured, searchable format would improve transparency and oversight.

Jose Mujica, the former Uruguayan president (2010-2015), was known as the “world’s poorest president”. Embracing a philosophy of anti-materialism and public service, he reportedly donated 90% of his presidential salary to charity and chose to live on a small family farm rather than in the presidential palace. He once summed up his thoughts on wealth, saying: “I don't feel poor. Poor people are those who only work to try to keep an expensive lifestyle, and always want more and more.“

While we could dream of a world where all elected officials eschew wealth and privilege, in South Africa, members of parliament, like all citizens, are allowed to engage in lawful business activities. Prohibiting them from doing so would be unconstitutional.

The average annual salary for an MP is R1.3m. If one would poll the country, a general consensus would surely be that they earn too much and while that salary places them securely in the 1%, the tenure of any parliamentarian is precarious. With employment only guaranteed for five years, a desire for financial stability and future security is both prudent and understandable. It is however foundational that a member’s business interests do not conflict with their roles and duties as parliamentarians or that their position as parliamentarian is not exploited for personal gain.

Conflicts of interest can and do happen. For instance, is it possible that a member’s directorships of multiple import and export businesses could be in conflict with their position on the Portfolio Committee on Trade, Industry and Competition?

Or that a member’s activities in a Portfolio Committee on Police might be influenced by their advisory role in a firearm liability insurance scheme that helps in case of unlawful arrest by the SAPS.

Declarations

To avoid a conflict, parliamentarians agree to a Code of Conduct that includes a directive that they will declare all interests outside of parliament to the office of the registrar of member’s interests. Interests to declare include:

- benefits and interest-free loans (Unless it’s from a family member)

- consultancies or retainerships

- contracts

- directorships and partnerships

- gifts and hospitality (over R3000)

- income-generating assets

- ownership in land and property

- pensions

- remunerated employment outside parliament

- rented property

- shares and other financial interests

- sponsorships

- travel

- trusts

The register of member’s interests is published on parliament’s website every year and the public is then free to scrutinise the declarations of any member.

While this poses as tangible oversight and transparency, we should note the clause that “lifestyle audits are risk-based and not all disclosures will be audited” - which basically translates to “if it looks like a duck and sounds like a duck” and leaves the register as more of a formality and afterthought than a robust tool for accountability (which, we will argue, it potentially can be).

It’s there for all to see. Sort of.

The tokenistic pretence of the register is evident in its presentation and accessibility on parliament’s website. Can we search for a member of parliament and see every share they have or every gift they’ve received? Can we find all members with directorships and shares in a specific industry? Can we search for all international trips?

No.

There are no categories.

There are no names.

There is no search box.

There is just a PDF.

Well, to be fair, a list of PDFs.

To be able to analyse or gain any meaningful insight, data needs to be in a structured format that we can ultimately import into a spreadsheet or database. A PDF, by default, even if well-structured, makes this task harder and the register of member’s interests is not well-structured and makes it almost impossible.

It is ironic that South Africa’s government is committed to "e-governance" and digitizing public services—yet critical transparency documents remain analog.

It’s not just them

Years of corruption and state capture have destroyed our trust in government. Hindering our access and scrutiny of the register feels like deliberate obfuscation, but the South African parliament is actually following the international trend. Countries like Australia and New Zealand also only present member’s interests in PDF format. When countries, like the UK, do provide a digital, searchable format, it also lacks consistent structure that prevents easy analysis and understanding. This either suggests that, at best, parliaments globally do not see much use in improving public access or, at worst, it is any government’s default position to avoid scrutiny.

A comprehensive survey of how different parliaments’ share and report on member’s interests would be useful and fascinating.

The worst book club

With declarations on contracts, land ownership, travel and gifts, the register itself can tell us a lot about the activities, habits and character of our elected officials. It can potentially reveal a trail of favours and friendships long before any concerns are raised, but without any obvious way to explore and parliament’s reluctance to audit, the register only becomes useful when a member has already been considered high-risk.

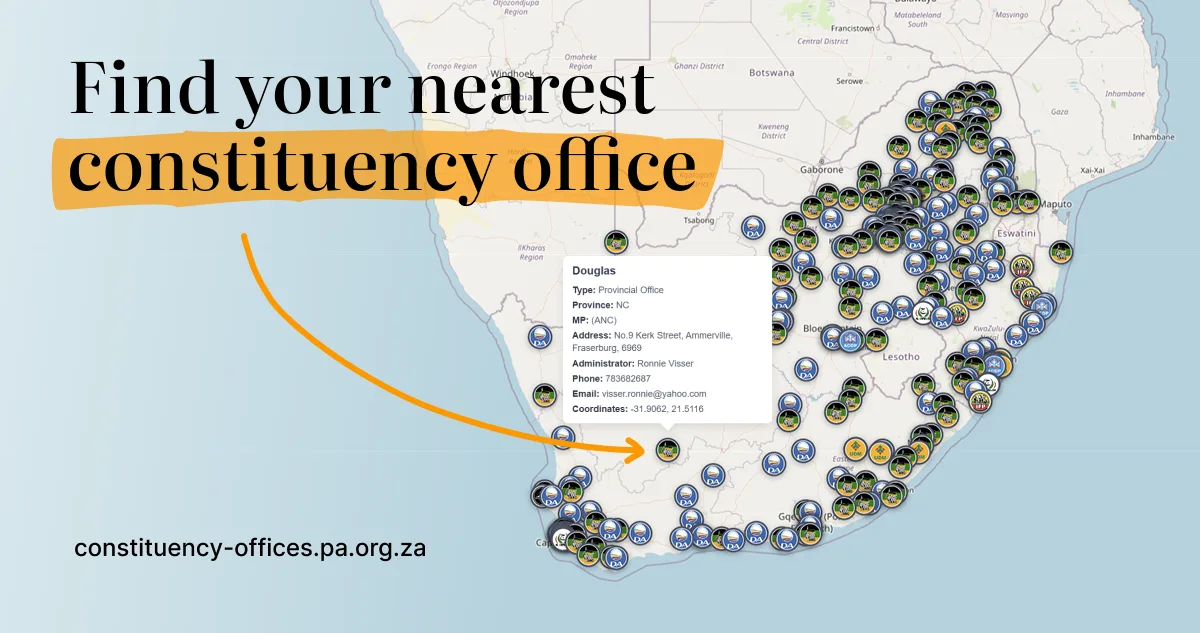

Over the last few years PMG and OpenUp have developed a workflow to extract data from the register. The People’s Assembly website is currently the only place where one can view the interests of any individual member.

This workflow has required writing scripts that scrapes the PDF register and converts it into a structured format. The script looks for repeating patterns and attempts to isolate every individual’s interests and then to group and categorise them. But the script is only as good as the PDF’s patterns are predictable. The script is not guaranteed to work every year as any change in naming conventions or formatting will break the expected pattern and require refactoring.

Even with successful scraping, the lack of consistency in the register makes data cleaning and analyses unnecessarily difficult and time-consuming. For instance, when a member has nothing to declare for a specific category, the register might record this as “Nothing to disclose”, “N/A”, “None”, “No”, “Non” or even just blank. We also find cases where values end up in the wrong columns and inconsistent use of monetary values and sizes are too common.

This misses a great opportunity for better oversight and insight and we shouldn’t have to read through a 400+ page document to get this information.

For instance, according to a 2020 research brief by the SA-TIED (Southern Africa – Towards Inclusive Economic Development programme), “...in 2017, the top 1% of South Africans in terms of net worth owned 95% of the bonds and corporate shares in the economy.” While parliamentarians only make up a fraction of the elite, the fact that only 27% or parliamentarians have declared any ownership of shares seems misaligned with their socio-economic class and, perhaps, an interesting area for study. On the other hand, a third of parliamentarians declared 2 or more properties with 9 parliamentarians declaring more than 6 - a spread which seems well within reason.

Gifts and travel are often tools of persuasion. The register suggests that soft diplomacy is, first and foremost, concert tickets and desk ornaments and though we do see the odd sponsored trip from China (youth forum) or Russia (film festival), in 2024, there were only 33 declared trips split between 26 parliamentarians (6%). This seems suspiciously low and one can only surmise that there is confusion about what type of trip needs to be declared and what falls in and out of the allowed work trips allotment. Here’s an idea - just declare every trip.

Similar confusion is evident in the declarations on income generating assets where most entries are repeat listings of share holdings, rental properties or pensions already declared in other sections.

Recommendations

The register’s free-form formatting suggests that the entries are being captured in a document rather than through a form.

A form could pre-populate category fields, but also options for known entities such as tax-registered businesses, countries and embassies. Currently even common businesses are spelled differently throughout which adds an additional cleaning task before any meaningful analysis is possible.

Property sizes and monetary values should be consistent.

There seem to be no guidelines on the use of quantitative values in the register. Stricter use of monetary and size values would allow us to easily see outliers.

The categorised data should be filterable and searchable on parliament’s website. It should also be downloadable in clean CSV files for further analysis and exploration.

A clean and consistent register will enable parliament and tools like Parlimenter to easily define and flag potential conflicts of interest.

An audited register with honest and comprehensive declarations will provide essential oversight of potential conflicts of interest and valuable insights into the parliamentary class.

Work with us

We are looking for resource and data partners!

If you or your organisation would like to contribute or collaborate, please get in touch.

You might also like

Global Ethics Day 2025 and South Africa's Parliament

What goes into Monitoring Parliament? Behind the scenes with PMG’s Monitors!